Comparing and judging ourselves negatively

Do any of these thoughts sound familiar to you?

- They’re better conversationalists than I am.

- I’m not as interesting and knowledgeable as they are.

- They’re better looking. I’m not in their league.

- They’re much more successful and impressive than I am.

- They come across as so confident, and I come across as so nervous.

- They’re so outgoing and charismatic. I’m so shy and anxious.

- They’re much better with people than I am.

- They’re more likable than I am. They have better personalities.

It’s very common that socially anxious persons spend a lot of time–and experience a lot of distress–comparing ourselves negatively to others. Sometimes we do this before a conversation or other activity we are anxious about: worrying how we’re going to come across compared to others. Sometimes we do this self-comparison during a conversation or activity: trying to figure out what impression we’re making compared to how well others seem to be doing. And sometimes we ruminate for long periods after a conversation or activity: fretting or beating ourselves up about the bad impression we fear we made compared to how we think others came across.

Maybe you don’t directly compare yourself to others so much, but you still criticize yourself a great deal. You may put yourself down, often quite harshly, with thoughts such as these:

- I’m bad with people.

- I bad at making conversation, especially small talk.

- I’m not interesting / attractive / successful / smart / confident / likable …

- I’m not good enough.

All these harsh self-judgments are implicit comparisons of ourselves to how we think we should be, and to how we imagine the kind of people we admire actually are.

Whether we are comparing ourselves negatively to others, or we are directly judging ourselves negatively, we are acting on the core belief that we are fundamentally deficient, and are not good enough to be respected, like or loved by the people we admire. It’s easy to see how this core belief generates a lot of social anxiety, shame and depression: the unhealthy triad that often goes together.

Why are we doing this to ourselves?

Self-comparison and self-judgment are types of safety-seeking behaviors that socially anxious persons rely on in an effort to prevent or minimize our fears from coming true. Safety-seeking behaviors are crutches we lean on too much because we hope they help us in risky situations.

Some such crutches are external and obvious, such as avoiding activities–or avoiding saying or doing things within those activities–that we fear may lead to embarrassment, judgment or rejection. Other crutches are internal and much less obvious, such as the tendency of socially anxious persons to self-monitor our feelings, symptoms, appearance and performance during conversations and other activities in an effort to prevent coming across badly. Or we may devote more effort to trying to guess the other persons’ reactions to us than we do to fully engaging in the conversation. Or we try to subtly conceal our anxiety symptoms. Or we try to keep the conversational attention on the other persons by asking lots of questions and saying very little about ourselves.

Negative self-comparison and self-judgment is an internal safety-seeking behavior that it is aimed at trying to prevent us from appearing or behaving in ways that will create a bad impression. By highlighting in our minds what we think is wrong with us, we hope to hide or correct these deficiencies. If we just ruminate long enough and hard enough about our deficiencies, then maybe we can correct or conceal these flaws in the future. We judge ourselves in an effort to prevent others from judging us, which we imagine would be more painful.

Sounds useful, no? Well, actually, no! Like all other safety-seeking behaviors, self-comparison and self-judgment is highly self-defeating. Although intended to protect us from the pain we fear in others’ judgments, we end up unintentionally causing ourselves far more pain in our own self-judgment, and the self-defeating behaviors that result.

Here are examples of the consequences of relying on the safety-seeking behavior of negative self-comparison and self-judgment:

- It results in frequent feelings of shame, hopelessness, worthlessness and depression.

- It severely erodes our self-confidence and greatly increases our social anxiety.

- It leads us to avoid participating fully in conversations and other activities in which we fear our deficiencies may be revealed.

- It leads us to rely on self-monitoring and other safety-seeking behaviors during conversations and other activities in an effort to conceal our deficiencies.

- This reliance on safety-seeking behaviors results in hurting our performance and appearance during conversations and other activities, because it distracts us and inhibits us from engaging fully.

- All of this prevents us from being able to learn that others generally react positively to us, and that we can handle it well when they don’t.

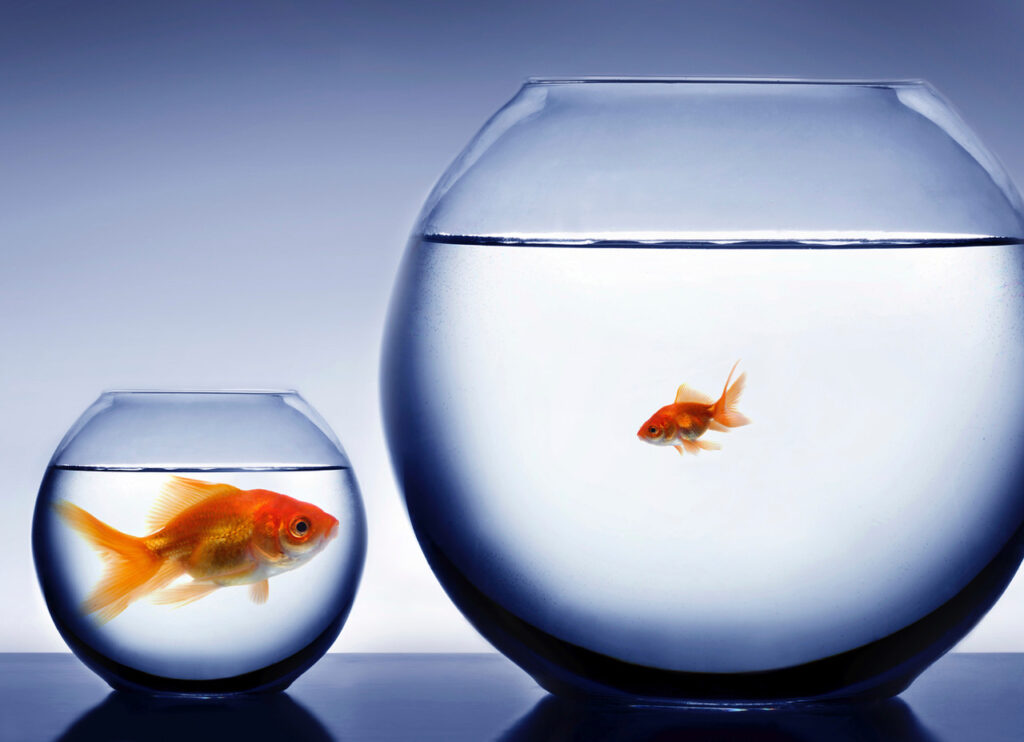

Unfair, distorted, double standards

Besides being severely self-defeating, our self-comparisons and self-judgments are not even fair! They are highly distorted and biased. We are comparing our (perceived) weaknesses to other peoples’ strengths, while we disqualify–or don’t even notice–our own strengths.

Our comparisons and judgments are also unfairly based on the double standard of forgiving the weaknesses of others while harshly condemning our own. We expect perfection in ourselves, but not in those people whom we admire.

We also assume that other people have the same unforgivingly perfectionistic standards about us that we do. We assume that any supposed flaw in our appearance or behavior will lead others to harshly judge us because we spend so much time harshly judging ourselves for such flaws.

It would be one thing if our comparisons and judgments were constructive, and actually led to self-improvement and enhancement of our lives. Maybe then it would be worth it. To the contrary, however, our self-comparisons and self-judgments are self-destructive, leading to shame, depression and anxiety, and resulting in lives that are stuck and severely inhibited.

Judging others

A minority of socially anxious persons have a double safety-seeking behavior: not only do they compare themselves negatively to those they admire, but they also compare some other people negatively to themselves. By looking down on others they view as less than, they feel better about themselves in compensation for feeling less than the people they look up to.

Well, only temporarily! Judging others as inferior is small compensation for feeling inferior to those whom we admire! Like all safety-seeking behaviors, judging others backfires: it reinforces the belief that we are not good enough compared to the people whose approval and acceptance we long for.

This view of human worth as some sort of ladder, in which we occasionally get to look down on those we see as beneath us, only ends up strengthening our social-anxiety-causing belief that the people we admire are looking down on us!

The alternative: CBT for self-acceptance, self-confidence and pride

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), demonstrated by a great many studies to be the most effective treatment for social anxiety, offers a number of strategies to help combat this problem of negative self-comparison and self-judgment. Here’s an outline of some of these strategies, below. Try them out on your own or, better yet, work together with your cognitive-behavioral therapist to help you practice these strategies in a series of therapy homework experiments.

PRACTICING CURIOSITY TRAINING / EXTERNAL MINDFULNESS:

Get out of your head and into the moment! Practice “curiosity training” during all conversations and other interactions, especially when you feel anxious. Practice getting absorbed / engrossed / lost in the conversation or activity in the moment, while you defuse from troubling thoughts and feelings. In other words, treat your self-comparisons and self-judgments as unimportant background noise, and return your attention to taking interest in the conversation, the activity, and the persons with whom you’re interacting.

This takes practice, as social anxiety draws us inward to focus on our self-critical thoughts and anxious feelings. Please follow the steps in the attached handout on Mindfulness Practice for Social Anxiety for detailed instructions on how to practice curiosity training, both while observing and while participating. Also, this earlier blog article further describes how to practice curiosity training with thought defusion.

CONDUCTING BEHAVIORAL EXPERIMENTS:

Design and conduct a series of behavioral experiments in which you are putting to the test your negative self-comparisons and self-judgments, and the fearful predictions they generate. For example, if you repeatedly compare yourself to others whom you believe to be much better conversationalists than you, and you repeatedly judge yourself to be uninteresting and unpleasant in conversation, then your fearful predictions may be that those with whom you are conversing will react negatively to you. Perhaps you fear they’ll make facial grimaces or negative comments, and that they’ll end the conversation abruptly, all because they find it unpleasant to converse with you.

Treat these self-comparisons, self-judgments and fearful predictions as hypotheses. Test these hypotheses out in a series of conversational experiments. It’s very important that you practice external mindful focus during these experiments: getting absorbed in the conversation in the moment while treating your negative thoughts and feelings like background noise. Also, drop any other safety-seeking behaviors you tend to rely on as a crutch during conversation: such as speaking very briefly, asking lots of questions, or scripting what to say next. Leaning on these crutches will result in your learning less during the experiments.

Complete the first part of the attached Experiment Worksheet before conducting the experiment, and then complete the remainder of the worksheet as soon as possible afterwards. Read the attached sample worksheet to understand how to use this tool. Using the worksheet will help you learn more from the experiments, and will help you make more progress in reducing your self-comparisons, self-judgments and social anxiety.

Your behavioral experiments will generate evidence refuting your fearful predictions and the negative self-comparisons and judgments that generate these anxious predictions. Conduct a whole series of behavioral experiments through which you are gathering more and more evidence to weaken your self-criticism, making sure you are increasingly mindfully focused and dropping other safety seeking behaviors during these experiments.

Our earlier blog article describes more in detail how to choose and conduct behavioral experiments.

BEING A GOOD PARENT TO YOURSELF:

There’s a very common risk that, after conducting our behavioral experiments, we slip back into periods of ruminating about how we think we didn’t do well, and comparing ourselves negatively to others. We take a step or two forward by doing the behavioral experiment, but then take a step or two backwards by returning to self-comparison and self-judgment. We need to learn to pat ourselves on our backs, rather than beat ourselves up!

I call this being a good parent to yourself. Unlike an emotionally abusive parent who harshly criticizes their child for not doing well enough, and for not doing as well as someone else, a good parent affirms their child for their positive efforts, and suggests ways they can do even better next time. This is what we need to practice for ourselves in order to build self-confidence and personal pride, and to reduce social anxiety and shame.

After every behavioral experiment or unplanned challenging experience, follow these steps:

1. Affirm all the positive things you did during the experiment or other experience, no matter how small or incomplete. Be specific, and write these down.

2. Rather than criticize yourself or compare yourself negatively to others, identify what you can learn from this experiment / experience, and what you might want to do differently next time to put into effect what you’ve learned. Write this down, too.

3. Don’t ruminate! Instead, refocus your attention on an activity you value and which captures your attention, and treat your self-comparing and self-judging thoughts like background noise. If those thoughts keep haunting you, remind yourself that you have already learned what you can from this experiment / experience, and that rumination only makes you feel miserable and diminish the progress you’ve made. Reread your positive actions and learning points (from #1 and 2), and then refocus mindfully on a valued activity.

This earlier blog article describes in greater details how to use this strategy of being a good parent to yourself.

KEEPING A PRIDE AND GRATITUDE LOG:

Living for most of your life with social anxiety (and perhaps also depression) has created a profound negative bias against yourself. You pay much more attention to what you perceive as wrong with you and how you think you come across, and you tend to not notice the positive, or disqualify it as somehow not counting. Keeping a daily Pride and Gratitude Log will help retrain your mind to pay attention to the positive about yourself and how you come across.

Every day, review in your memory all that you experienced and did during the past 24 hours, and write a list of anything that was in any way positive, no matter how small or imperfect. Then, for each positive item in which you participated, ask yourself what are the qualities or strengths about yourself that this represents, and write these down, too. For example, perhaps you had a pleasant conversation with a coworker or other acquaintance. Your underlying qualities that this represents might include: being a good enough conversationalist, and that some other people enjoy conversing with you.

It’s important to make entries in your log every day so that you are retraining your mind to pay attention to and appreciate the positive about your experience, yourself and how you come across. Definitely include the behavioral experiments you conduct in this log, so that you keep track of your positive qualities that these are highlighting. The attached Pride and Gratitude Log instructions sheet gives you more guidance in using this strategy, as does this earlier blog article.

GATHERING OVERLOOKED EVIDENCE:

Write out a list of people to whom you tend to compare yourself negatively. List each person’s positive qualities individually as you see it. Then, for each person, think about their negative traits that you dislike or at least don’t admire, and write these down, too. Follow up this exercise by spending a week or so looking for and thinking about additional negative qualities in these individuals, and anyone else you think of you tend to look up to, and write these down. During this same period, also record entries daily in your Pride and Gratitude Log, making sure you are identifying your own underlying qualities.

Do this exercise for just a week or so, and then drop the gathering of negative evidence of others while you continue the Pride and Gratitude Log to continue gathering positive evidence about yourself.

If you tend to compare some others as inferior to yourself to compensate for feeling inferior to those whom you admire, then do this exercise in reverse: spend a week or two looking for and thinking about their positive qualities and write these down, while continuing to make daily entries into your Pride and Gratitude Log.

The purpose of this strategy is to help us see people–those we admire, those we look down on, and ourselves–in a more realistic light: that we all display complex mixtures of desirable and undesirable qualities, rather than being superior or inferior in human worth.

DOING COGNTIVE RESTRUCTURING:

All the above strategies (except for mindfulness) are examples of doing “cognitive restructuring”: modifying our distorted thinking so that our perceptions and attitudes about ourselves are more aligned with real-life evidence. Another strategy to tackle your negative self-comparisons and judgments is to complete a Cognitive Restructuring Worksheet where, in step-by-step manner, you are learning to think about yourself in ways that are more realistic and helpful. There are also many smartphone apps that guide you in doing cognitive restructuring, such as CBT Thought Diary.

Attached is a version of a Cognitive Restructuring Worksheet, along with a sample and instructions. This earlier blog article describes how to use cognitive restructuring to help change your socially anxious thinking.

Written by Larry Cohen, LICSW, A-CBT

Cochair and cofounder, National Social Anxiety Center

Director, NSAC District of Columbia (Social Anxiety Help)

larrycohen@socialanxietyhelp.com; 202-244-0903